Players

Latest > Representing: Sam Snead

Jan 20th, 2016

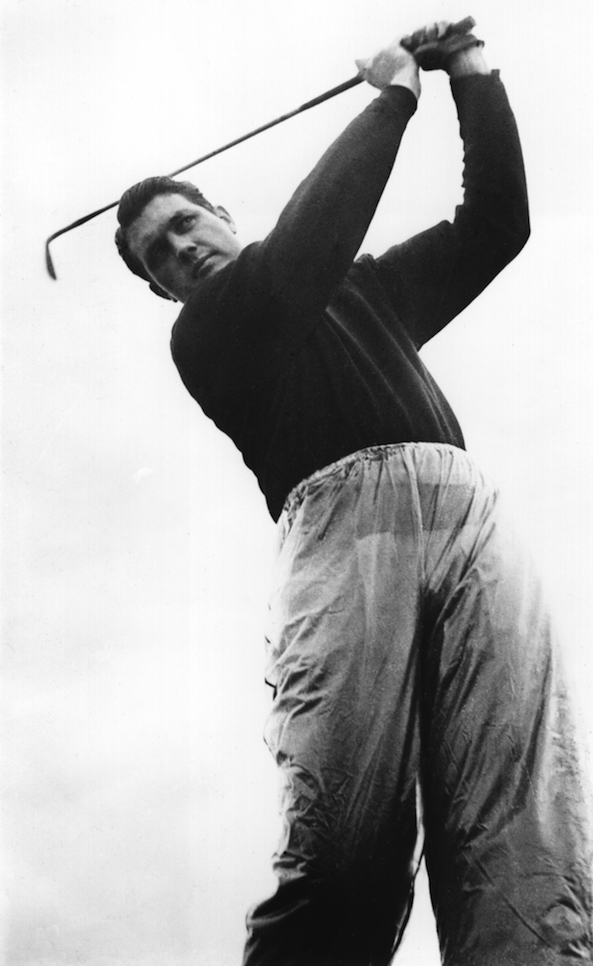

Representing: Sam Snead

Representing For The GolfPunks All Across The World

Words: Gavin Newsham Photography: Getty Images

It’s 1936 and 24-year-old Samuel Jackson Snead is making his first start as a professional at the Hershey Open in Pennsylvania. As he stands on the par-four first with his 1-wood in his hand, he tees his ball up, sets himself and swings, but his ball veers wildly off course and out of bounds. Nervously, he reloads, but once again his ball flies past the white posts and out of bounds.

Too lazy to read the article? Bit tired are ya? Well, here's a nice video on Slammmin' Sam.

As Snead reaches in his bag for another ball, the galleries begin whispering, wondering whether the young man’s professional career will ever get started. In a flash, though, Snead has teed it up again and launched it down the fairway. It eventually comes to rest nearly 350 yards away – on the green. Four days later, the young man from Hot Springs, West Virginia finishes fifth on his professional debut and so the legend of ‘Slammin’ Sam Snead is born.

Brought up on a farm in the Depression, Sam Snead spent his days doing what any other boy from the West Virginian woods did. He hunted and fished and when he could he caddied for cash at the local golf course just to help his family through the tough times. But football was his game and the young Sam had harboured dreams of one day making it in the pro ranks, until a back injury put paid to his chances. It was then that his older brother, Homer, suggested he try golf.

Without the funds for any tuition or equipment, Snead worked on his game using clubs fashioned from discarded club heads and tree branches, and practicing long into the night with only car headlights to help him see what he was doing.

By the time he joined the tour in 1937, he had already gained a reputation as the game’s next best thing. When the legendary Gene Sarazen first caught a glimpse of him he knew that here was a player that was going to make a huge impact in the professional game. “I've just watched a kid who doesn't know anything about playing golf, and I don't want to be around when he learns how,” he said. Sarazen’s hunch was right. At the end of his rookie year, the country boy in the straw hat had won five times, but it would take another 22 wins before he finally bagged his first Major at the 1942 PGA Championship. By then, though, everybody in the game knew about that swing. Long, elegant and almost effortless, it was the kind of action that left spectators speechless and fellow pros green with envy.

Like so many of his compatriots, though, Snead was always reluctant to make the trip to Britain for the Open Championship. It wasn’t just the travel or the courses or the smaller balls they used in Britain that kept the Americans away but also the comparatively meager prize money on offer.

When Snead finally made his debut in the competition at St Andrews in 1946, he would go on to win the Claret Jug and the $600 first prize, but he would leave having amassed over $2,000 in expenses for the week. For someone whose frugality was well known throughout the game, that represented a bad week’s work, even if he had landed another Major in the process. Indeed, when a reporter asked if he’d be back to defend his title at Hoylake the next year, Snead was as honest as ever. “No sir, 600 bucks is tippin’ money,” he insisted. “Why, I can take that off my buddies back home before lunch.” It would be 16 years before Snead returned to play in the Open.

Back on the other side of the pond, though, Snead had established himself as an equal partner in a triumvirate that seemed to take turns to rewrite the record books. With Ben Hogan and Byron Nelson, Snead stood out as the one with the swing sent from heaven. While his nickname ‘Slammin’ Sam’ didn’t really do justice to the aesthetic perfection of his swing –Snead actually preferred ‘Swingin' Sam’ – it did, however, reflect the prodigious distances he could launch a ball. Indeed, in an age when a drive of 220 yards was regarded as long, Snead’s natural rhythm coupled with his impeccable timing helped him routinely drive the ball over 270 yards.

In his book of 1946, How To Play Golf, Snead revealed the secret to his long-hitting. “Take it easily and lazily,” he wrote,“because the golf ball isn't going to run away from you while you're swinging.” While his assault on professional golf took a back seat during World War II –Snead spent over two years in the Navy – he soon carried on where he had left off, winning the first of his three Masters titles and the Player of the Year award in 1949.

By 1950, though, Slammin’ Sam had soared through the stratosphere. That year, he collected 11 tour titles, achieving a stroke average of 69.23 over 96 consecutive rounds. “I won a lot of tournaments because I was in better shape than the other guys,” he said. “I didn’t smoke and didn’t drink and went to bed at reasonable hours.”

To his chagrin, though, Snead would not retain the Player of the Year title in 1950, despite his record-breaking achievements. Instead, the honour went to his rival Ben Hogan, who had returned to action after a near-fatal car crash and, against the odds, won the US Open at Merion.

Snead would never win the US Open, the only blot on an otherwise immaculate copybook. Certainly, he had his chances, most notably in 1939 when he finished with a triple bogey when a par would have given him the title and then in 1947 when he led by two with three to play but missed a 30-inch putt on the 18th to hand the championship to Lew Worsham. “Sure, it bugs me they make sure a big deal of it because I never won the US Open,” he said, “but I must have been playing pretty good and sinking putts when I won those three Masters, three PGAs and the British Open.”

Possibly the only other complaint Snead could have had over his long and distinguished career was his performance on the greens; the older he got the more his putting deserted him. The net result was that he developed a unique style on the greens, a kind of ungainly croquet punt that was completely at odds with his fluid swing on the fairways. The decision to switch putting styles gave Snead a longevity few other players have enjoyed. Even when the authorities outlawed his new putting stance he simply switched to a new one whereby he stood face-on to the hole and putted from the side. Snead, though, was unfazed. “It’s not how,” he would say, “but how many.”

Snead died on May 23 2002, four days short of his 90th birthday. It was fitting that his last shot was at Augusta, the scene of his greatest triumphs. As the oldest living Masters champion, Snead had taken the ceremonial opening shot – as he had since 1984 – and so what if it smashed into a spectator’s face who was walking down the first fairway. At least, as Sam later reflected, he “got it off the ground”.

Snead’s record of 82 tour titles (11 more than Jack Nicklaus) remains head and shoulders above any other challenger and his swing remains one of the finest that ever existed. At Snead’s funeral in his hometown of Hot Springs, West Virginia, PGA Commissioner Tim Finchem fought back the tears during his eulogy. “No one will ever duplicate Sam Snead. No one will ever surpass Sam Snead, because,” he concluded, “Sam Snead was so unique.”

Related to this story: