Players

Latest > Representing for all the GolfPunks: Dai Rees

Oct 18th, 2017

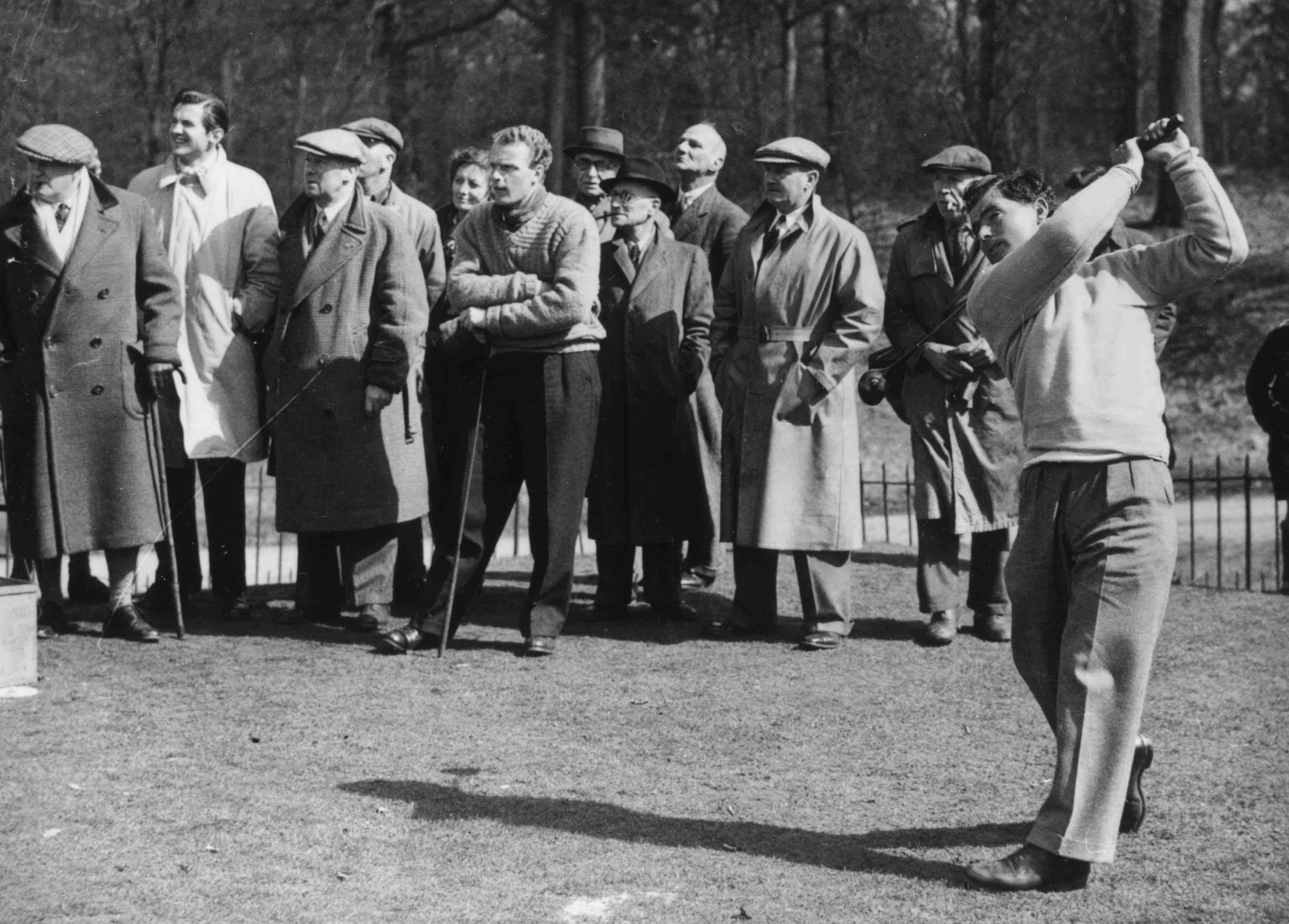

Representing for all the GolfPunks: Dai Rees

The dudes who come correct and represent golf as it should be...

Photography: Getty Images

Dai Rees was our original Ryder Cup gangster. A veteran of nine cups as a player and captain no less than five times, the canny Welshman’s no-compromise style of leadership inspired his Great Britain and Ireland team to one glorious, against-the-odds triumph in an otherwise unrelentingly humiliating sequence of 19 defeats (and one tie) between 1933 and 1985. He got a CBE for his efforts - frankly, he deserved a knighthood.

Dai Rees was our original Ryder Cup gangster. A veteran of nine cups as a player and captain no less than five times, the canny Welshman’s no-compromise style of leadership inspired his Great Britain and Ireland team to one glorious, against-the-odds triumph in an otherwise unrelentingly humiliating sequence of 19 defeats (and one tie) between 1933 and 1985. He got a CBE for his efforts - frankly, he deserved a knighthood.

Rees was also a mad-keen Arsenal football fan; his death in 1983 came as a consequence of injuries sustained when he crashed his car on the way back from watching a game. He had been a regular at Highbury for many years and even trained with the first team to keep himself fit in winter. In return, he would welcome Gunners players for rounds at South Herts, the club where he served as professional for 37 years having taken over from the great Harry Vardon.

Regrettably, Rees’s death at the age of 70 meant he never saw his one great wish fulfilled – to see the Ryder Cup back in European hands. Only two years later, however, at the Belfry, the hoodoo was finally broken, the dam unleashed, and Samuel Ryder’s trophy was regained. Amid all the wild and frankly drunken celebrations, a story about that unforgettable day reveals just how deep Cup fever (that’s Ryder, not FA) ran in Rees’s blood.

The European team, led by Tony Jacklin and featuring another, even more pint-sized Welsh hero in Ian Woosnam, were celebrating their spectacular 16½-11½ victory with a variety of tipples including a particularly fine bottle of pink champagne – but no one knew the identity of its provider. Then a tour official revealed it was none other than the late Dai Rees, who before his death had arranged for the bottle to be presented to the first European team that managed to win back the infernal Cup. Talk about an inspired round.

“Dai had phenomenal enthusiasm for all aspects of the game,” recalls former European Tour chief Ken Schofield, who would regularly catch the train up to South Herts for a game with the 60-something Rees. “He would be off teaching and playing tournaments non-stop, then still be out on the Monday morning trying to qualify for the next one. Today’s professionals would laugh at the very suggestion.”

Rees’s professional career is inevitably dominated by his Ryder Cup achievements, and especially that famous win of 1957 at the fine Yorkshire course of Lindrick. Amid angry scenes that show the Cup’s recent arguments over rowdy players and fans are nothing new, Rees skippered his GB&I side to victory over the US for the first time in 24 years – and the Americans didn’t like it at all.

As the visitors saw their 3–1 lead slide to a 7½-4½ defeat on the final day of singles, American moods darkened considerably. Cleverly, Rees had put the ultra-competitive Eric “Bomber” Brown up against the famously irascible Oklahoman Tommy Bolt, who was duly wound up, breaking a club and cursing the sizeable (and admittedly partisan) Yorkshire crowd as he went down 4&3.

“You may have won,” Bolt is said to have told the victor through gritted teeth, “but I did not enjoy that one bit.” To which Brown bluntly replied: “After the whipping I gave you, I wouldn’t have enjoyed it either.”

Another less-than-gracious loser, Dow Finsterwald, declined to shake hands with Christy O’Connor Snr after being buried 7&6, while no less than three Americans are said to have ducked out of watching Rees accept the Ryder Cup trophy. But for all this bad grace it was, without question, the Welshman’s finest moment in golf, and one of the towering achievements in Ryder Cup history. An emotional Rees himself called it “the greatest shot in the arm British golf ever had”.

A measure of what the win meant to the public on this side of the Atlantic was Rees’s receipt of the BBC Sports Personality of the Year awards at the end of 1957 - a far more significant honour than the CBE he received in the New Year’s Honours list, of course.

By then acclaimed throughout Britain as one of the greats of his generation, the unassuming Rees had long been a hero back home in Wales. Born in 1913, he grew up the son of the professional at Aberdare Golf Club, a course famous for its mature oak trees and heavily-cambered fairways. He is said to have bogeyed the first hole he ever played as a child, and was not long into his teens before he began applying to enter national amateur tournaments. Bizarrely his requests were rejected because of his father’s status, so Rees Jnr got the message and turned pro, becoming the assistant at Aberdare aged a tender 16 years.

Only 5ft 7in and not the most powerful of swingers, the Welshman had a fun-loving twinkle in his eye and a natural, smooth action which found a groove early in his career and stayed there for five decades. He was a great ball striker, not a tinkerer, and with that fierce determination won four British PGA Championships and was runner-up at the Open three times – in the process assuming the pre-Monty mantle of best golfer never to have won the Claret Jug.

His first “near-miss” at Carnoustie in 1953 was actually not that close – a flu-ridden Ben Hogan on his very first appearance was still far too good for the rest of the field, and the American beat Rees and others by four shots to achieve “the Hogan Slam” with his third major of the year.

But a year later at Royal Birkdale, with Hogan having remained in the US, Rees came agonisingly close to the title, co-leading after the third round and missing a putt on the 72nd hole which, it turned out, would have put him in a play-off with the Australian winner Peter Thomson.

Rees’s finest Open battle, however, came when the rota returned to Birkdale seven years later. It was against another American legend-in-the-making, Arnold Palmer, who after surviving gale force winds that brought down marquees held a one-shot lead over Rees going into the final round. By the 14th hole the game looked up, Palmer (playing ahead) having stretched that

lead to four.

But Rees showed all his fighting spirit over the last four holes (not for nothing is he referred to as “the Welsh bulldog”) to eek back the lead until he was within a shot of young Arnie. It was just too little too late, however, and Palmer clung on to win his first Open Championship in typically rollercoaster fashion. As for Rees, his chance of Open glory was now gone.

Later that year he yet again led the GB&I Ryder Cup team into battle, this time at Royal Lytham where he immediately came up against Palmer in the morning foresomes. Rees lost out again, and the British could not repeat the heroics of four years earlier. It was Rees’s ninth and last time playing in the event; in all he contested 17 matches and won 7½ points including five singles victories – a fabulous record given the overall one-sidedness of the event back then. Rees went down in a blaze of glory too, taking three points out of four in that final 1961 edition.

There was even a swansong in Houston, Texas, six years later, by when the idea of non-playing captains had been adopted. In that role Rees found himself up against the great Hogan again, and an American team which their captain confidently introduced at the eve-of-event dinner as “the finest golfers in the world”. And so it proved: Britain were crushed 23½ to 8½, the biggest ever losing margin and a poignant end to Rees’s extraordinary Ryder Cup career.

Not that Rees’s enthusiasm for the game dimmed one bit. He served as captain of the PGA from 1967 to ’76, and was still competing on the tour well into his sixties. In fact he finished joint runner-up in the 1973 Martini International in Edinburgh aged 60, and played his last tour event five years later, having won 39 tournaments during his illustrious career.

“You really couldn’t find anyone with more enthusiasm for golf – and life,” Schofield says of Rees. “At a time [in the early 70s] when John Jacobs was working hard to make the PGA European Tour into a business, it was vital to keep sponsors and the media happy. And Dai was always there to do his bit.” Rees’s legacy was especially remembered when Europe prevailed again at the K Club in September 2006 under the captaincy of Woosnam, for whom Rees was a huge inspiration as a child. When the champagne flowed, it was only be fitting to sink another bottle of the pink stuff in honour of this original Ryder Cup legend.

Related to this story: