Players

Latest > Representing for all the GolfPunks: Charlie Sifford

Feb 21st, 2016

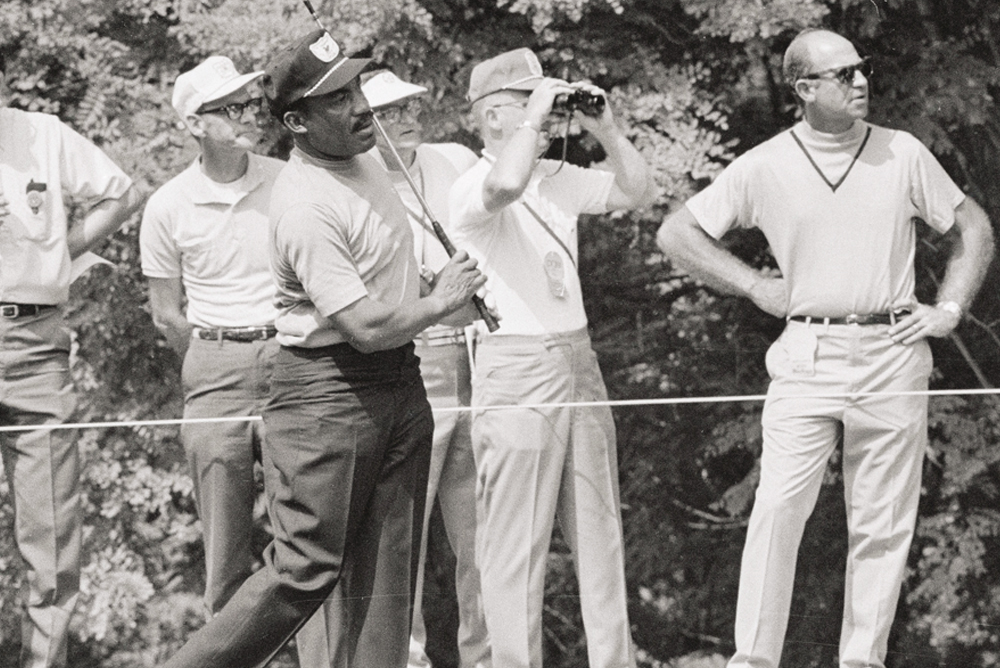

Representing for all the GolfPunks: Charlie Sifford

This guys changed the world and then some...

Words: Gavin Newsham Photography: Getty Images

When Charlie Sifford, the PGA’s first black member, was inducted into golf’s Hall of Fame in November 2004, he was introduced by his long-time friend, Gary Player. “Imagine Tiger Woods and Vijay Singh ranked the No 1 and No 2 golfers in the world being told they can’t play because they are black,” said the South African legend. “It’s hard to imagine what once happened in our world.”

Video: Remembering Charlie Sifford's Legacy

But happen it did and Charlie Sifford was on the frontline. As a black pro golfer trying to make a living in 1950s America, where segregation was still part and parcel of everyday life, Sifford’s opportunities to play the game he loved were limited, not least by a clause in the PGA’s membership criteria denying entry to black people.

But golf was the only game for Charlie Sifford and nobody was going to stop him playing. Once, when Sifford met Jackie Robinson, the first African American to play Major League baseball, Robinson had warned him what to expect as he embarked on a career in professional sport. “He asked me if I was a quitter. I told him no,” recalls Sifford. “He said, ‘If you’re not a quitter, you’re probably going to experience some things that will make you want to quit.’”

Soon after the meeting, Sifford discovered just what the baseball legend had meant. At the 1952 Phoenix Open, Sifford led off with three other black players. When the foursome reached the first green, they took the flag out to find human excrement in the hole. After an hour’s wait, the hole was eventually removed and replaced. Then, at the North Carolina Open, Sifford took to the tee at one of the par threes to find that the banner advertising a $100,000 prize and a new car for a hole in one had been removed for him. Undeterred, Sifford stepped up and aced the hole anyway. Not surprisingly, the incident would end in court years later with Sifford eventually receiving his prize.

While Robinson’s words of advice for Sifford were welcomed, there was a world of difference between their chosen sports. Robinson, for example, had played his baseball in public parks. Sifford, meanwhile, had chosen the worst place imaginable to ply his trade – the all-white preserve of the country club.

Undeterred, Sifford persevered but with his career path curtailed by the PGA’s Caucasian-only clause, he was forced to play on the United Golf Association (UGA) Tour, a minor circuit that offered only modest prize funds. Like many players on the UGA, Sifford supplemented his income by giving lessons. He would even take the job as coach to the jazz singer and keen golfer Billy Eckstein.

Like many black golfers of the era, Sifford had begun playing when he was a caddy. Growing up in North Carolina, he would carry bags at Charlotte’s Carolina Country Club, earning $1.50 on a good day.

As the years passed, his talent became obvious to anyone with a passing interest in the game and when he turned professional, it was only a question of when, and not if, he would win his first tournament.

In 1952, he claimed the first of six National Negro Open titles and managed to win $1,500 in three of the UGA events that were co-sponsored by the PGA. By 1957, Sifford’s form was so commanding that he comfortably claimed the Long Beach Open, and in doing so became the first African-American to win a PGA co-sponsored tournament.

As Sifford’s stock rose, and the American civil rights movement gathered pace, so too did the clamour for him to play on the PGA Tour. In 1960, the PGA finally bowed to the growing pressure and removed its Caucasian-only clause and in doing so granted Sifford his playing rights, making him the first black member in its long history. It also made him a 41-year-old rookie. That said, Sifford’s membership did not come with full privileges – he would have to wait a further five years for those – and still he would have restricted access to the clubhouses and locker-rooms of the professional game.

Slowly, though, Sifford found that more and more of his tournament applications were being approved, but despite the apparent change in attitudes across the game those competitions based in the notoriously racist southern states were still holding out against him. In 1961, though, one of the PGA tournaments in the South – the Greater Greensboro Open –finally allowed Sifford to play. While it was a breakthrough, it was still clear that his place in the starting line-up was not some tacit form of acceptance but merely a measure to appease the PGA and those pressure groups seeking change.

Prior to the event at the Sedgefield Country Club, Sifford received death threats over the phone and then, during the first round, he was pursued around the course by a gang of 12 white men, who abused him relentlessly and repeatedly kicked his ball into the rough. That he finished the tournament was testament to his unbreakable fortitude. That he finished fourth was just remarkable. “I felt a larger victory,” he said later. “I had come through my first southern tournament with the worst kind of social pressure and discrimination around me and I hadn’t cracked. I hadn’t quit.”

While Sifford’s breakthrough was rightly heralded as a new dawn for professional golf, it would be six years before he made the all-important step up to PGA Tour winner. It came on August 20 1967. Faced with a four-foot putt for par and a final round 64 at the Greater Hartford Open, Sifford rolled it home for a one-stroke victory over a field featuring Arnold Palmer, Lee Trevino, Gary Player, Ray Floyd and Tom Weiskopf. As the crowd at the Wethersfield Country Club rose to their feet, Sifford broke down. He was still crying when they gave him the trophy.

Sifford’s single-minded determination to break into an almost exclusively white world would soon open the door for other black golfers on the PGA Tour. From Pete Brown, first black winner on the PGA Tour at the 1964 Waco Open, to Lee Elder, the first black player to tee it up at Augusta in1975, each owed a huge debt to Sifford. “Without Charlie Sifford there would have been no one to fight the system for the blacks that followed,” says Elder. “It took a special person to take the things he took. Myself, I don’t think I could have taken it, because I’m a little too thin-skinned. Charlie was tough and hard.” Tiger Woods has also paid tribute to Sifford. “If it wasn’t for Charlie,” he once said, “we wouldn’t be here.”

While Charlie Sifford would only win two events on the regular PGA Tour (his other victory being the 1969 Los Angeles Open), his name will nevertheless go down in history as one of the game’s true champions; a man who almost singlehandedly hauled the professional game out of its shameful past into a future that offered hope and opportunity to all players, regardless of colour.

At his induction into the PGA Hall of Fame, Sifford reflected on a lifetime spent trying to right wrongs. “There is always a way to forgive but I cannot forget what I went through to get to the Hall of Fame,” he reflects. “I know I had some bad days, some tough days. But it looks like everything turned out fine.”

Related to this story:

Representing: Lee Elder takes up the Charlie Sifford mantle

Representing: The Slammer Sam Snead and his remarkable life

Representing: Max Faulkner - 50 cigarettes a day and little practice = superstar

Representing: Gary Player asks us to punch him in the stomach!

Representing: Dai Rees the legendary Welsh Ryder Cup hero

Representing: How Bernard Gallacher went from Wentworth pro to Ryder Cup legend

Representing: JH Taylor - along with James Braid & Harry Vardon, one part of The Great Triumvarate